I I am pleased to share with readers excerpts from a note sent in September 2020 to GlobalSource Partners subscribers upon the release of the Development Budget Coordinating Committee (DBCC FRS) Budget Risk Statement. Christine Tang and I, assisted by Charles Marquez, are their Filipino advisers.

DBCC FRS 2020 (https://www.dbm.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/DBCC_MATTERS/FiscalRiskStatement/Fiscal-Risks-Statement-2021-for-Circulation.pdf) outlined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the government’s fiscal health over the medium term. Below are our key takeaways from fiscal risks to watch over the medium term. (In truth, the finance / economics team of the next administration has their work cut out for them!)

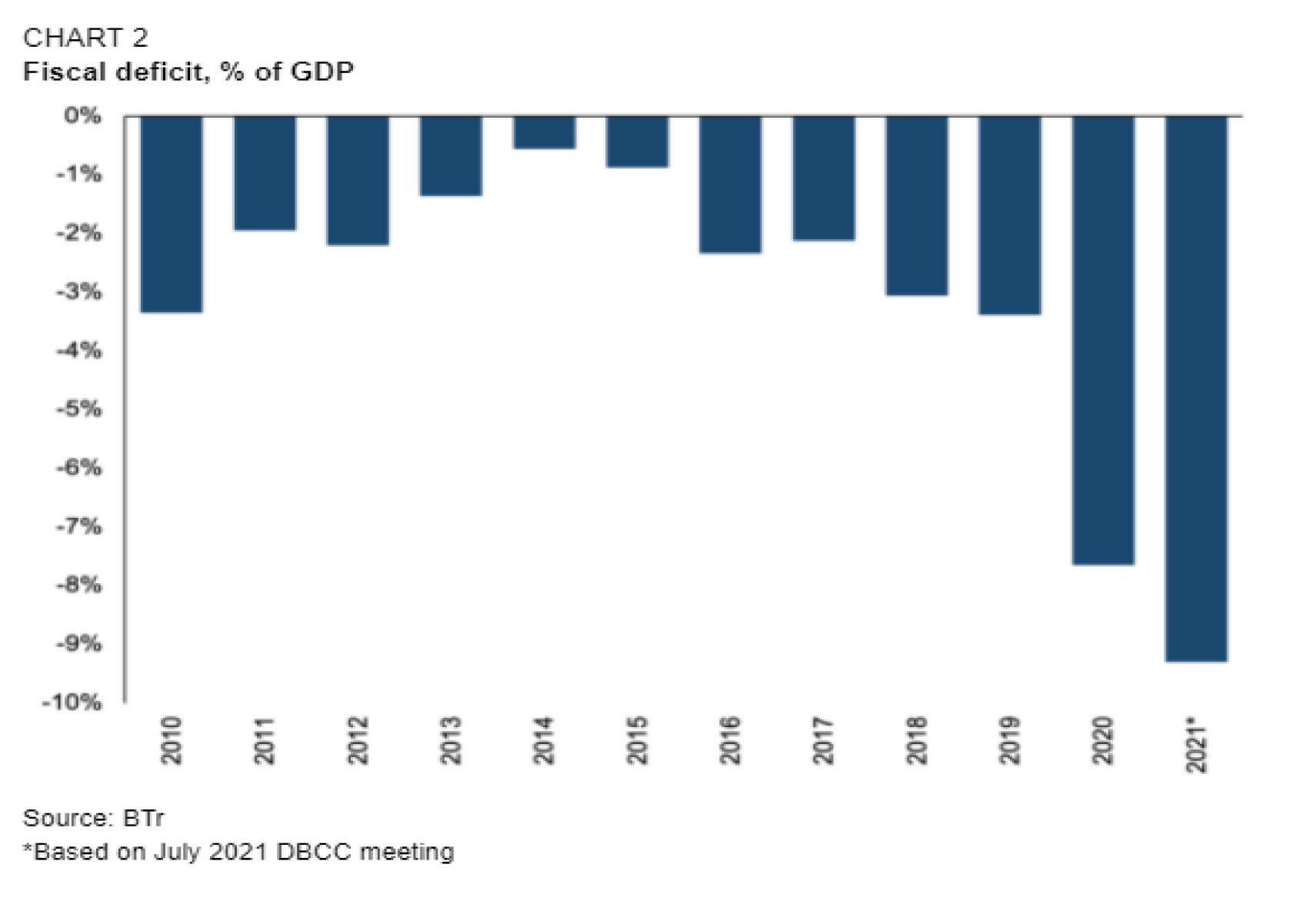

1. DBCC expects government debt-to-GDP ratio to drop from less than 40% last year to 53% this year. because of emergency borrowing to finance the suddenly larger budget deficit. The debt ratio will continue to climb with a “moderate risk†of exceeding 60% as of next year. Reversing a downward path in the debt ratio depends on the medium-term return of GDP growth and the budget deficit to their pre-crisis averages.

The increase in debt will need to be watched more closely as it translates into much higher gross annual financing needs, exceeding 10% this year and next. Refinancing risks are partly mitigated by looser monetary policies everywhere that will keep interest charges low, with the share of foreign currencies accounting for only about one-third of total national government debt, part of which is owned by residents. The Philippines also has a strong external payments position which provides fundamental support to the currency.

2. National government revenue, which is expected to drop to 13.6% of GDP this year or 2.7ppt below pre-crisis level, will not return to pre-crisis levels for the foreseeable future. Following the declaration of the state of emergency, the government was able to obtain more than 100 billion pesos (0.5% of GDP) in unscheduled income from public companies in the form of dividends. This amount is unique, with non-tax revenues expected to be 1% of GDP lower by next year. The adoption of CREATE lowering corporate taxes will further erode tax revenues with offsets from streamlining tax incentives that are expected to be pushed back. No new tax is likely in the context of the current economic crisis, especially with the administration in its penultimate year.

3. With lower revenues, fiscal space for discretionary spending is expected to shrink further. Even before the pandemic, the national government was already grappling with how to manage (a.) The increasing retirement costs of military and uniformed personnel, estimated at 114 billion pesos (around 0.6% of GDP) and increasing by 3-4% per year, and, (b.) a Supreme Court ruling (Mandanas case) requiring increased annual transfers to local government units amounting to 0.9% of GDP from 2022. In the future, interest payments on the larger national debt will occupy an increasing share of the budget (from 9.5% in 2019 to 12.9% in 2022) which is, however, much lower than the share of 30%. recorded in the mid-2000s. On the other hand, some reduction in infrastructure spending can already be observed in programmed disbursements falling to 4.5% of GDP by 2022, against more than 5% in the year. next. Proposals on (a.) And (b.) Will become more urgent to allow the government to do more to accelerate post-crisis recovery.

4. Fiscal risks in other parts of the public sector have also increased in part due to the off-budget funding of COVID-19 spending. Social security institutions were the first to see surpluses turn into deficits (nearly 0.5% of GDP this year) due to significantly higher health and unemployment insurance payments, while the overall surplus of frontline local government units is expected to halve this year (from 1.3% of GDP in 2019) and deteriorate further next year to 0.5% of GDP. Governmental Financial Institutions (GFIs), in addition to granting debt moratoria and other temporary relief measures, are also called upon to finance the post-crisis recovery effort with the financial impact of lending activities and guarantee of development depending on the safeguards that will be put in place during the design of the program. Other large companies, particularly in the transportation (aviation, ports) and energy sectors, also saw their operating revenues fall with the economic contraction.

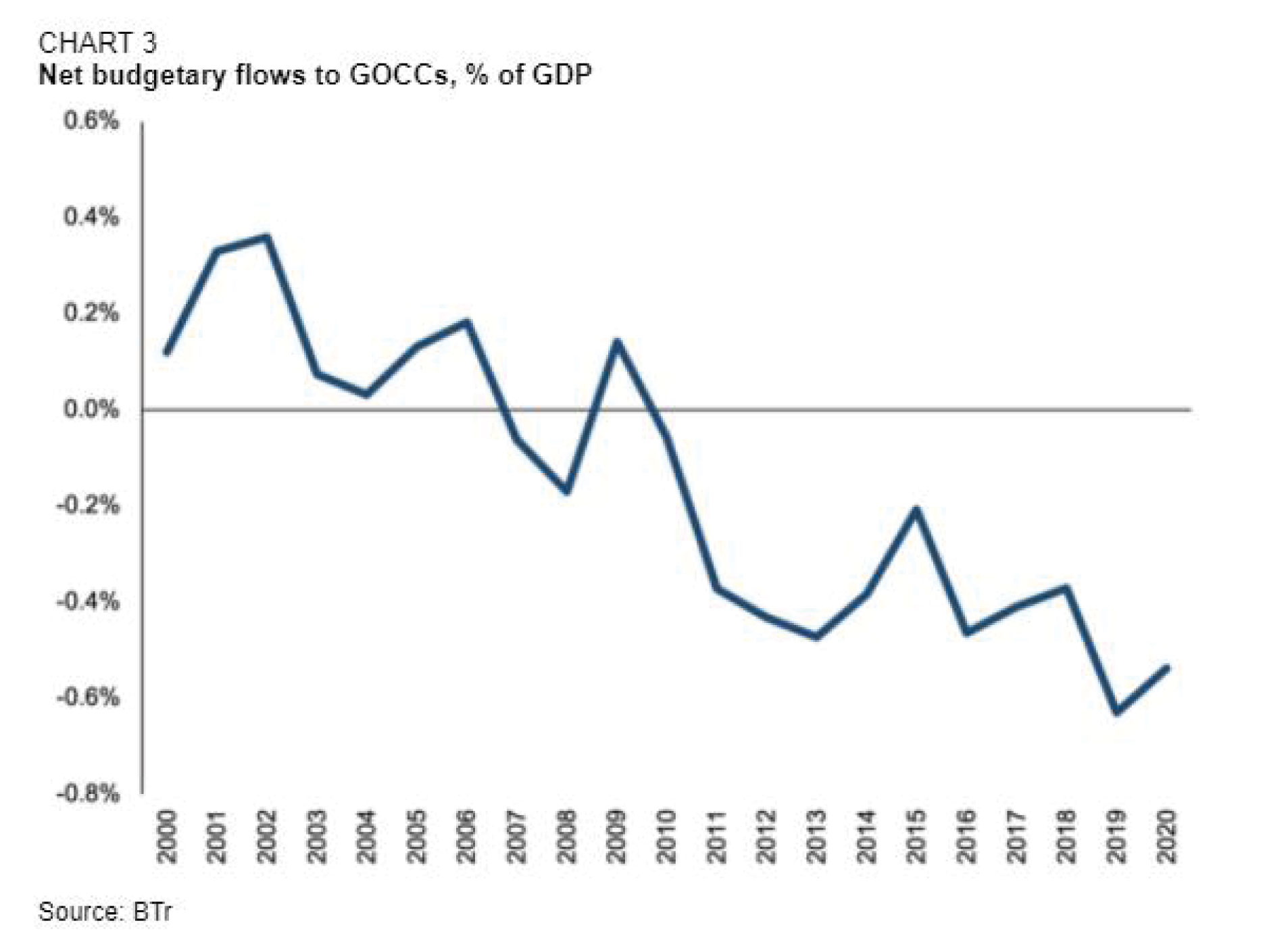

While most of these represent contingent liabilities that may never materialize, some parts would require major reforms to correct structural flaws and avoid recurring national government subsidies, equity infusion or advances for the government. debt service. (At the risk of requiring more support from the government at this time, the health insurance agency which, in addition to an increase in debts linked to COVID, will see its income fall with business bankruptcies and an increase in unemployment to the detriment of universal health care goals.) Even before the pandemic, the government had outstanding guarantees on public enterprise debts and contractual obligations equivalent to 3.3% of GDP that it was securing through “advances”. ‘rising to 1.4% of GDP in 2019. Over the past 10 years, net fiscal flows to the business sector have been negative, ranging from 0.1% to 0.6% (2019) of GDP.

Local government units would need special attention given their heavy reliance on transfers from the national government for operating income (60%) and with the expected increases in revenues from the Mandanas decision likely to increase. short-lived given the COVID-19 shock to the national government’s own revenue.

5. Contingent liabilities associated with contractual obligations under public-private partnership (PPP) projects should also be monitored. as the risks are expected to be correlated with the state of the economy, with the downturn negatively affecting project income flows and / or promoters’ balance sheets, thus potentially affecting the viability of the project. Based on the 41 projects for which information is available, the worst-case scenario involving termination fees will cost the government the equivalent of 1.7% of 2020 GDP, although an assessment of contingent liabilities based on factors of probable risk specific to the project gives an estimate that is only a tenth of that.

6. In addition to GFIs, the government also has explicit guarantees (via deposit insurance) and implicit guarantees on the rest of the banking sector. which require closer monitoring of individual and systemic banking risks, as the quality and profitability of assets deteriorate with a weakened economic outlook. Risks are mitigated by large capital buffers and increased provisioning for bad debts. At the start of the crisis, the capital adequacy ratio of the large universal / commercial banks stood at 16% (consolidated basis) with quality Tier 1 capital at 14%, well above the BSP (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas) and the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) prescribe thresholds of 10% and 8%, respectively. These banks also increased loan loss provisions by 64% in the year through July, providing more than 1.2x coverage for bad debts, up slightly from less than 1.1x at the end of 2019. While the risk of system-wide stress is low, it would nonetheless be impossible to rule out problems at the level of individual banks, especially those that have not developed strong credit disciplines. . In addition, the operational risks associated with cybercrime have also increased in importance.

VIEW OF THE RESULT

Thanks in large part to successive reforms since mid-2000 to strengthen public finances, the national government was well placed to respond to the crisis and is able to move forward to play a greater role in economic recovery. without sacrificing fiscal sustainability. The challenge is of course to optimize the use of scarce fiscal resources to generate immediate jobs, creating economic growth that can be sustained in the medium and long term. Moderately high sustained growth will help reduce the debt ratio thanks to higher tax revenues (and a reduction in the primary deficit) and a more positive interest rate differential. To this end, more urgent reform measures are also needed to increase the efficiency of public spending and investment, in particular to address the imbalance between transfers to local governments and decentralized functions.

At the same time, a more thoughtful and comprehensive analysis of the fiscal risks associated with the new programs needed to accelerate economic recovery and job creation, for example by providing liquidity to struggling businesses, would help manage and mitigate these risks over time and to avoid detrimental threats to fiscal sustainability. Finally, with the severe impact of the pandemic, particularly on the poor and with elections less than a year away, fiscal sustainability also requires increased vigilance on the part of economic managers to ensure that new social programs are not only timely and targeted, but temporary.

Romeo L. Bernardo was Undersecretary of Finance under the Cory Aquino and Fidel Ramos administrations.

romeo.lopez.bernardo@ gmail.com

Universo Viviente

Universo Viviente