Swiss Nobel Laureate Didier Queloz and Swiss-German astrophysicist Sascha Quanz plan to study the origins of life at a new center in Zurich. What exactly are the researchers hoping to find out?

This content was published on October 19, 2021 – 09:00

Michele Andina

The new Center for the Origin and Prevalence of Life is scheduled to open next year at the Federal Institute of Technology ETH Zurich. Collaborations with the British University of Cambridge are also planned. SWI swissinfo.ch met the brains of the new campus.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Didier Queloz, you received the Nobel Prize in physics for discovering the first exoplanet. What chance is there that life exists outside of Earth, perhaps on one of the exoplanets or on Mars?

Didier Queloz: I am absolutely convinced that there is life elsewhere in the universe. For the simple reason that there are too many stars and there are too many planets. So having life as a unique thing on Earth would be too rare to be possible.

SWI: As a scientist, how would you define life?

DQ: (Laughs) When you talk about the origin of life, that’s the most obvious question to begin with. There are two ways of looking at it. First, we know life as it is on Earth and can use it as a reference. And this is valid because the chemistry you have on Earth may have happened on another planet as well. So you are looking for something based on what you know about the Earth.

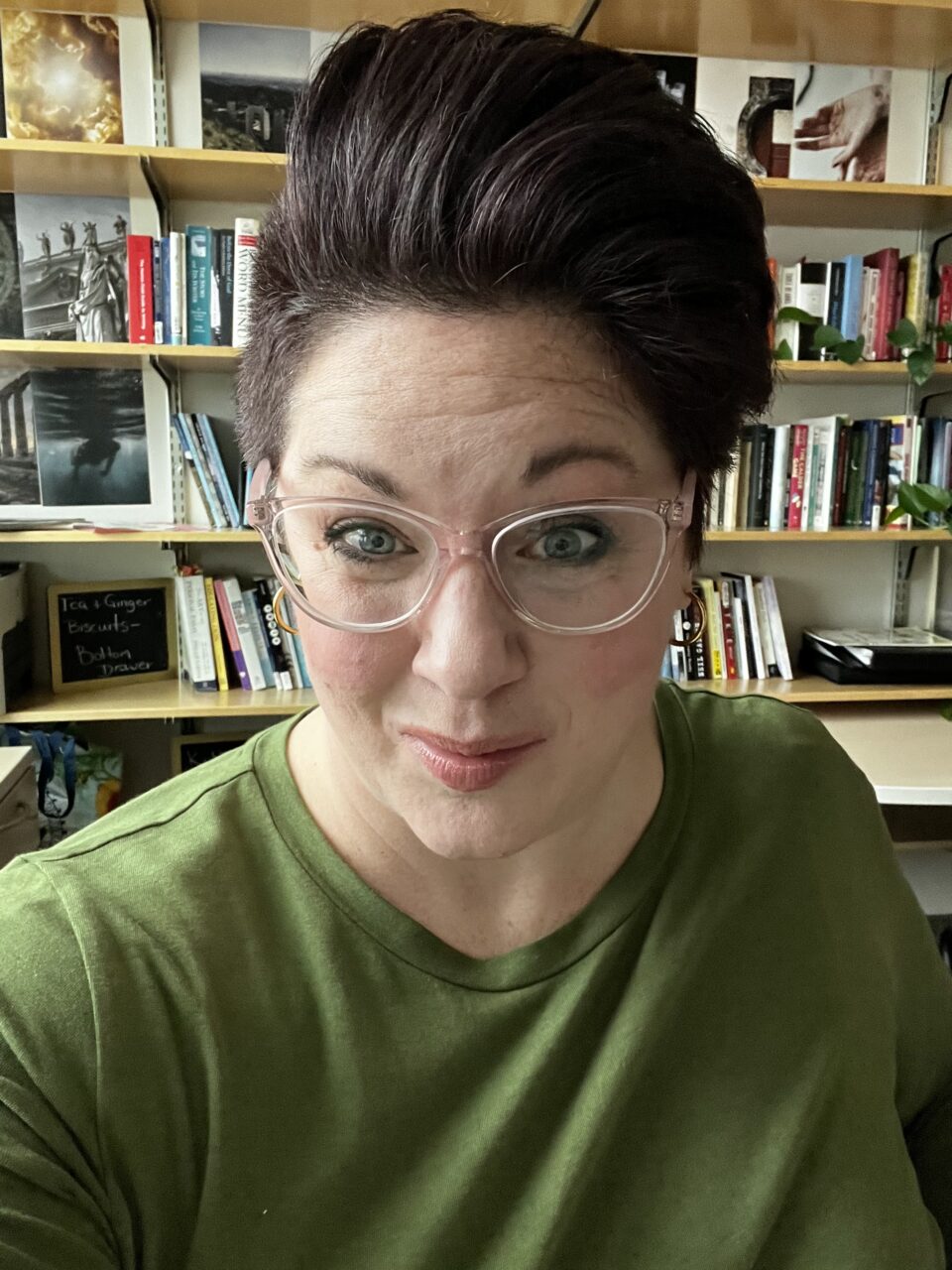

Didier Queloz

Born in 1966, Didier Queloz is a Swiss astronomer who discovered the first exoplanet in 1995 with his thesis director Michel Mayor. 51 Pegasi b is an exoplanet that orbits a star similar to the Sun.

According to experts, this is one of the most important discoveries of the 20th century in astronomy. It opened up new fields of research and massively increased the chances of finding alien life.

In October 2019, the two Swiss scientists received the Nobel Prize in physics for their research on exoplanets.

Queloz, previously professor of astronomy at the University of Geneva and the University of Cambridge, moved to ETH Zurich in 2021 to establish the research center and lead the management team.

End of insertion

Then there is the unknown: how can you identify life without knowing what it is? The most sensible answer is to try to see life as part of the planetary system. Life will at some point play a role in the history of a planet like on Earth, where oxygen is only the result of life.

So you would expect the chemistry of a planet to be somehow affected by life. The challenge will be to identify it. You may find that there is a characteristic that you cannot explain and may decide to call it “another life”.

SWI: Under what conditions can life be born?

Sascha Quanz: We don’t really know the answer. We know how life on Earth works and are starting to understand the initial conditions of how life started on Earth. But another question is: can you imagine other conditions? This is one of the questions we are trying to answer in the new center.

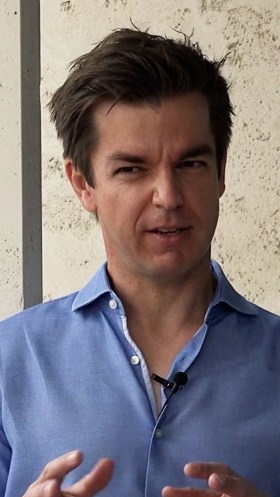

Sascha Quanz

Born in 1979 in Germany, the astrophysicist, also of Swiss nationality, obtained his doctorate at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. He arrived at ETH Zurich in 2009. In 2019, Quanz was appointed Associate Professor for Exoplanets and Habitability at the Institute of Particle Physics and Astrophysics at ETH Zurich.

His research group is involved in the development of instruments for the main terrestrial and space observatories to study the physical and chemical properties of extrasolar planets and their formation process.

End of insertion

SWI: You said we need to know more about the origin of life on Earth. Would it be possible to create life in the laboratory?

DQ: Technically, you could “reverse engineer†the origin of life. You can try to go back to the beginning, like when you take a car apart and learn how to rebuild it. I think people agree that until someone creates some sort of life in a lab, we don’t really know where life originated.

SWI: Why is the topic of life elsewhere so interesting to humanity?

SQ: I think this is one of the most fundamental questions that humanity has literally been asking for centuries. One of the other questions you might ask yourself is, why is this so important right now?

There are different places in the international academic landscape where people come together to address these questions. It is a combination of advancements in different areas of research. It took a while, but we have established some concepts well enough.

I think the time has really come to start interdisciplinary research, because we will be stuck if we do not bring in colleagues from other disciplines.

SWI: in June, ETH Zurich and the University of Cambridge will open new centers, an idea you both came up with. Interdisciplinarity is a key element of these centers, is not it ?

SQ: Anyone who is interested in the subject is welcome to join and be a part of the game. We’ll start with what I would say are the most obvious disciplines: chemistry, biology, earth sciences and astrophysics.

However, we also talk to scientists about environmental systems, people who understand the climate of this planet, for example. It could also be very useful to guide certain reflections, certain ideas. We will have to see who is interested in the subject. I would say, the more the merrier.

SWI: So, different researchers are going to start talking together at the coffee machine in the new center?

SQ: (Laughs) Yes, different disciplines approach the question of the origin or prevalence of life in different directions. People realize that at some point you’ve just hit a block. You cannot continue because you do not have the expertise, knowledge or data that can be provided by other disciplines.

The coffee machine will be a means of ensuring sufficient interaction and communication. When you embark on such an interdisciplinary task, you need to make sure that people start talking to each other. You have to get rid of your specialized tongue. You try to break it down to a level that everyone can really understand, and only then can you spark new ideas and can really develop new research.

SWI: Didier Queloz, you will be the director of the center. What are your concrete projects?

DQ: We have millions of concrete plans. This is exactly the problem we are facing right now. I think the creativity and what we want to do is way too big and way too big for the number of people we have. For example, we plan to have some ability to study rocks that will be brought back to Earth from Mars.

What we’re trying to do is not just create facilities and provide access. The idea is to open up a new field of research by opening up avenues for young researchers to develop and then go elsewhere to form new groups.

SWI: What’s the point of working with you?

DQ: There are a lot of people who are very curious about what is going on. We will do our best to make sure we build up enough momentum. It will be a question of money at some point. We must therefore offer something to these young people. Getting people out of their comfort zones isn’t easy, but there is so much to discover. So let’s have fun and do it together.

SWI: How important will this center be for the Swiss scientific community?

DQ: In terms of scientific quality, Switzerland is extremely well placed in the world. So you would expect the country to research the main topics. And this is one of them. Switzerland has a high academic level, funding and a quality of research that you will not find everywhere.

I think having the theme of the origins of life in Switzerland will attract people from abroad. We will attract students, perhaps junior faculty positions. We will attract people who might not have considered going to Switzerland in the first place. I think this will have consequences for the country in general, because these people will teach, they will help build knowledge that will sooner or later go into the industry.

Even today, in a situation where Switzerland is struggling to find its precise relationship with the European Union, I think that having an extraordinary scientific objective helps to forge links with industries, with other universities and d ‘other countries. So we bring some inspiration to the company. And this is something that should not be overlooked. Because inspiration makes a society happy and alive.

Universo Viviente

Universo Viviente